By Ivette Lampl, M.S., LPC-S, LMFT-S, Experiential Group Therapy Program Manager

When my kids were babies and toddlers, I would take them grocery shopping with me. I’d put the cushioned seat cover in the cart, and we’d walk through the aisles together. Sometimes I’d talk out loud while putting items in my cart. Sometimes my kids would ask for an item, and we’d either add it to the cart or have a little conversation about why we weren’t buying it. These little experiences were a time of bonding, a time where my children learned about the regular things that people in society do. They weren’t big, lifechanging events, but they were small opportunities for them to be present in the real world.

This week at my local grocery store, I saw a new style of carts for adults with children. This cart has the child sitting low, below the groceries, where the child can’t see anything but people’s legs and the bottom shelf. And this version has a screen that plays digital entertainment for children while the adults shop.

As a mental health professional, my first thought was: What is going to happen when the parent has to take that child out of the cart and put them in the car? How will they survive the drive home (if they don’t provide another screen for that)? What about when this child has to stand in line or wait for a table at a restaurant? If we put screens in front of children at every opportunity, we take away the natural balance of the brain to support cognitive and emotional regulation.

This isn’t just my opinion. The use of constant digital consumption is chemically altering the brain in a way that I wish we all understood a bit better.

There is a very important chemical in the brain called dopamine. In simple terms, dopamine is what allows us to feel pleasure and provides motivation. It’s often called the “feel-good” hormone. We get a surge of dopamine when we engage in a pleasurable activity, such as eating a favorite food, sex or seeing a favorite show.

The challenge we are starting to see in the mental health world is that we are now getting our dopamine from alternative sources, namely technology. The kid in the grocery cart… slightly bored? Turn on the screen, and there’s a hit of dopamine. The teenager sitting alone in their room scrolling TikTok… sees a funny video, hit of dopamine. I see teens in my practice who, when they are supposed to put their phones away, just keep it right next to them. They just want to see their phone, tap it, check the home screen. These tiny interactions with their devices are all tiny hits of dopamine.

Why does this matter?

The brain and body are constantly working to achieve homeostasis, the “just right” balance between two opposites. For example, the regulation of our body temperature is a form of homeostasis – sweating or shivering are two ways our body responds to achieve balance when the core body temperature changes. The brain also has built-in mechanisms to achieve homeostasis.

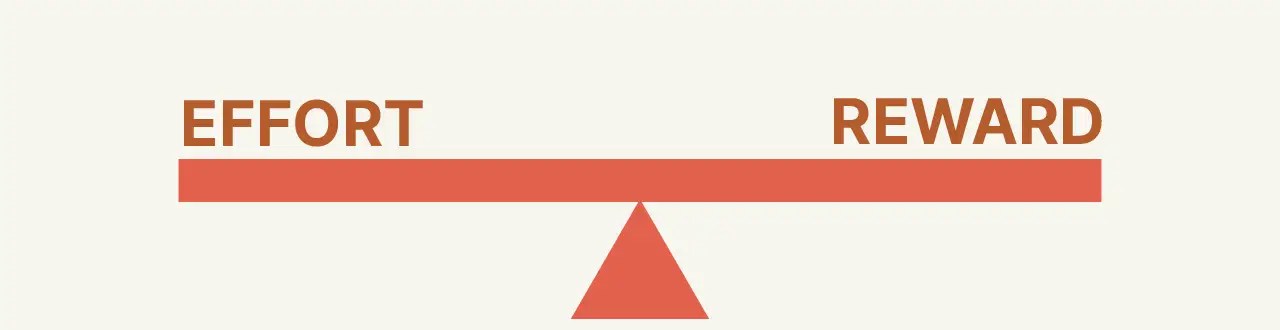

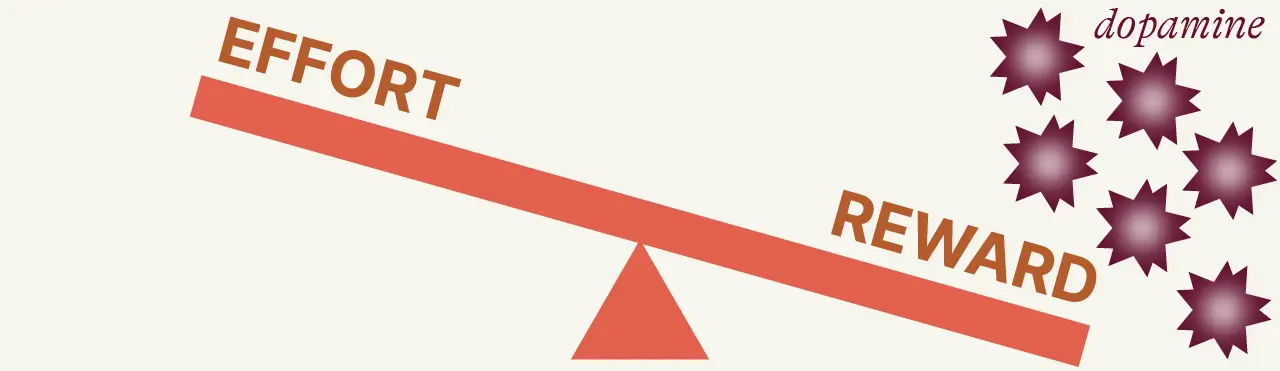

When it comes to dopamine, homeostasis is found in the balance between effort and reward. The brain is wired to function like this: put in effort – achieve reward. Cook up a tasty snack? Enjoy the yummy treat. Hike up a steep hill? Take in the scenic view from the top. Effort – Reward.

It may seem like the more pleasure you experience, the happier you will be. This isn’t quite the case. Even in the brain, there is truth to the saying “too much of a good thing.” If your brain is receiving pleasure all the time, it will begin to think that it has plenty of dopamine and it will produce less.

So now we’ve entered a new cycle. Reward – Reward – Reward. The brain gets hit after hit of dopamine and it is on a continuous mission to seek more pleasure.

Technology has allowed us to eliminate the effort part of the Effort – Reward cycle. No need to cook a meal – just have it delivered! No need to drive around town looking for the perfect dress for an upcoming event. Just open your favorite shopping app and several options can be at your front door by morning.

Now add in a layer of dopamine hits that we get from our minute-by-minute interactions with our devices. Likes, comments, notifications, messages – all of these are tiny doses of dopamine that we ingest all day long. When the brain senses that there is an abundance of pleasure without the effort/challenge to offset it, it decides that there is too much dopamine and it needs to produce less. And without the brain’s production of dopamine, we begin to seek out more dopamine from external sources, and this cycle continues.

Think of it like this. Let’s say you’ve gone on a long walk on a hot day, and you treat yourself to a scoop of ice cream. Amazing! The brain receives a dose of dopamine and all is well. Now let’s say you really enjoyed that ice cream, so the next day you help yourself to a large scoop while watching TV. No problem. But the next day, you crave ice cream so you eat it directly from the carton. By the end of the week, you’re eating a pint every day. The ice cream is no longer pleasurable, now it is necessary to counterbalance the effect of the pain you experience when you don’t have your ice cream.

So now think of a teen who goes home after school and sits on the couch scrolling through videos, flipping between apps, and texting their friends. This child is getting hit after hit after hit of dopamine. And this can go on for hours with no break! Then an adult tells them it is time to put their phone away and do their homework. The brain – flooded with dopamine – is now trying to rebalance itself. It prepares for the discomfort of withdrawal, the struggle of homework. The child doesn’t like this feeling at all, because it is uncomfortable and hard. So the child doesn’t put the phone away. They sit to do their homework, but they pop over to their phone every minute or so. They can’t focus and the ability to concentrate and put in the effort is not just a difficult task, it is painful.

If this sounds familiar, it is because the cycle is very similar to addiction to substances such as alcohol and drugs. Dopamine is created when we experience pleasure. For a person who is struggling with addiction, the brain chemistry has changed because the person is engaged in activities or substances that release dopamine. When the substance or activity goes away, the brain is not able to release enough dopamine to counter that absence. The person experiences significant pain because they are not able to have the source of the dopamine or pleasure. This leads to withdrawal and cravings, and thus the cycle of addiction.

There are four symptoms that are common in people who have developed a dependency on a substance or behavior: anxiety, irritability, depression and cravings. If you have spent time with a teenager who has a dependency on using a smart phone or video games, when adults try to set limits or take away the phone or computer, you have likely seen all four. These symptoms are often the reasons that adults bring their teenagers in to our clinic for mental health services. They say their child is always irritable, the child doesn’t want to come out of their room, they won’t talk to them, they’re always angry. Add to that the other factors affecting our youth, the experience of trauma, stressful environments, peer conflict, and the list goes on. As mental health professionals, we can no longer treat these symptoms without understanding the impact that excessive digital use is having on their brain. Just like we wouldn’t overlook an addiction to substances.

So what are we supposed to do with this information?

In substance addiction, the answer lies in abstinence for enough time (which varies case to case). The brain has to have enough time without the substance to recover its natural ability to achieve homeostasis. This is a hard sell for teens and families – but one that might be necessary if there is a strong dependency. At first it will be difficult and painful but with the right support, people can achieve freedom for the need to be on their devices. Once the brain regains its balance between pleasure and pain, we can begin to engage in the behavior with new boundaries and considerations that will support our wellbeing.

Here are a few suggestions on how to break the addiction to devices and reset the brain’s natural balance.

Turn off notifications

When I meet with clients, children or adults, I ask them if they have notifications on their phone. If they say yes, I ask how often during the day they receive notifications. More than 10 a day? 20? 50? Many teens are receiving more than this in a single day – nearly constant notifications popping up on their device every hour. I tell them that when they’re trying to focus on something like homework, but their phone next to them is constantly lighting up with another notification, it’s like someone tapping them on the shoulder. Would they be able to focus if someone was standing next to them tapping them on the shoulder every few seconds while they worked? Of course not, but the phone is essentially the same.

Have uninterrupted focus time

I encourage teens to start small with tasks or activities they can do without their phones. Engage in cooking, music, art, reading or another hobby without a phone present. Start with ten minutes and then give yourself permission to check your phone for three minutes. Work your way up to 15 minutes, stopping to check your phone for three, then up to 20 minutes. If ten minutes to start seems impossible, try five. Just try something to get started and you can build your tolerance over time.

Reset

This tip is especially helpful for teens who are addicted to video games. Online gaming is especially challenging because it is social in nature. Teens are using games to connect with their peers, and because they’re playing together, it is reinforcing to continue to play for hours without breaks. For these kids, I recommend a hard stop with no playing time for a set amount of time. This can vary based on the person and the situation. Experts in addiction generally say that a hard stop should be at least 15 days. There will be a trial and error in this process, because for some people, it may take longer. This break can help get the game addiction out of the system and regulate the dopamine in the brain. When the child engages again, start with one hour on and one hour off. Set a timer because it can be easy to lose track of time while playing.

Immediately after taking the electronics away, kids and teens may be irritated and agitated. This is not the best time to establish boundaries. Instead, a period of withdrawal may be necessary. And it may not be fun! The child may struggle with behavior outbursts. After a period of detox, the child will likely be ready to re-introduce the technology with new limits and boundaries. Adding something that will help the kids stay socially connected will be important during the time they are not playing their social games.

Encourage pretend play

Younger kids, around 7 and under, learn through pretend play. They see their dad sweeping the floor and they grab an object and pretend it is a broom. They see their aunt cooking and they go to work in their toy kitchen. This is essential for cognitive development. In today’s world, many adults hand their children a device or allow them to engage in screen time to occupy them while they take care of adult tasks. This is completely understandable, as adults have a lot to do and kids can definitely be a distraction. But the downside to this is that kids are missing out on the opportunity to be creative and engage in pretend play. Through this play, they activate neural pathways in the brain that are essential for cognitive skills, including the process of imagination. They also experience bonding with their caregiver that helps deepen the relationship. This play doesn’t have to be structured or set up for the child – just giving them plenty of time without devices to be bored and come up with ways to entertain themselves using materials around the house is great for the developing child.

Seek challenge

Our brains are not designed to have this much pleasure without the counter-balance of effort. I encourage teens to seek challenges that will help with this balance and will ultimately make them more content and satisfied. This can look like trying a new hobby that is slightly difficult, engaging in exercise or a form of movement that is slightly strenuous, or sitting calmly through a mindfulness practice. Any of these can be uncomfortable or even painful in the moment, but can help the brain reach that level of homeostasis.

Have open communication about the impact of technology on the brain

Children and teens are smart enough to understand that the phone can re-wire their brain in a way that can be unhealthy. Explain to them the link between technology and dopamine and help them understand that their actions influence their brain in a tangible way. When kids have agency over their brain, they can grow to make better, more informed decisions as they enter adulthood.

Share with

Related Resources