Dacher Keltner from UC Berkeley, and author of The Power Paradox: How We Gain and Lose Influence (Penguin Press, May 17, 2016) shares his thoughts on viral compassion in this guest blog post.

--

For the past 20 years, I have studied a deep irony in our social lives, the power paradox. The power paradox is this: We gain power and the capacity for influence through social practices that advance the interests of others, such as empathy, collaboration, open mindedness, fairness, and generosity. And yet, once we gain power, success, or wealth, those very practices vanish, leaving us vulnerable to impulsive, self-serving actions and empathy deficits that set in motion our fall from power. For example, studies find that as we enjoy elevated power or rise in the social class ladder, we are more likely to lie, cheat, shoplift, eat impulsively, have sexual affairs, violate the rules of the road, take candy from kids, and communicate in disrespectful ways, all acts that diminish dramatically our capacity for influence. These abuses of power, a number of studies find, not only undermine the quality of our work lives; they also are harmful for our relations with romantic partners and our kids. In fact, in my new book “The Power Paradox: How We Gain and Lose Influence,” I summarize studies showing that how we handle our power is one of the most important determinants of our happiness and that of people around us, that what we do with power says a lot about the state of our society.

How can we find good power in our personal and professional lives? On this question, science has produced a surprise – we make the most of our power through compassion. Namely, acts of compassion produce viral cycles of good will that not only bring out the best of those around us, but create a foundation for our own good power.

For example, in the behavioral economics literature this principle goes by the name of competitive altruism. Competitive altruism refers to how people rise in power through acts of compassion, kindness, and generosity. Relevant studies find that as people share more and express greater kindness, they actually rise in the esteem of others and enjoy elevated power. By contrast, people who defect on others or horde resources for themselves suffer stinging losses to their reputation and a reduced capacity to influence.

Far removed from these laboratory studies of competitive altruism, anthropologists have uncovered a similar dynamic in who rises in the ranks in small hunter-gatherer societies, living in the conditions in which we evolved for over 200,000 years. It is not the selfish Machiavellian who prevails. No, once again status and power go to the individual who shows the greatest compassion and kindness, who shares the most, in the form of food, labor, and the provision of protection and care. The compassionate givers, this science shows, enjoy better status, increased mating opportunities, and their kids tend to be healthier as well. This should not surprise: groups are served well by individuals who direct resources to the group, and collectively encourage such kindness through directing esteem and affording power to the more generous.

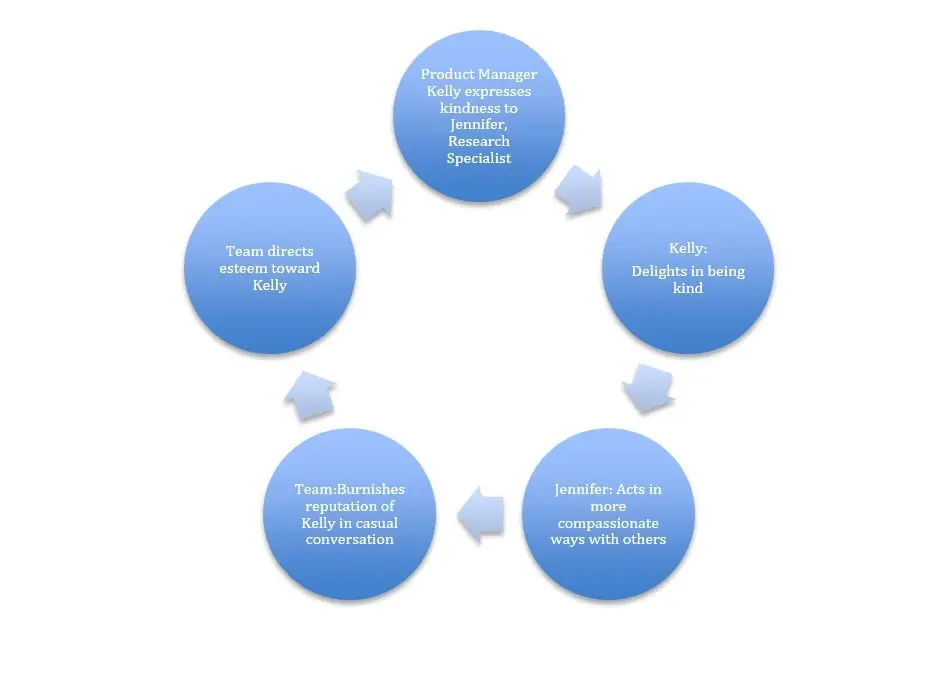

New studies in social psychology have pinpointed how we gain power by through viral acts of compassion. The simple story is that when we act in compassionate fashion, by sharing for example, or attending to someone in need, or expressing gratitude, those acts stir others to greater collaboration, which set in motion downstream social processes that bolster our reputation, a critical foundation of our power. I’ve diagrammed this dynamic in the figure below, and illustrate with an example that comes from the workplace, but it could just as easily extend to our relations within families, or with neighbors in our community, or with fellow friends in a social organization.

At the top is a manager – in our example Kelly – who acts in a compassionate way toward a research specialist, Jennifer. In the example it’s a heartfelt expression of kindness – perhaps she takes a bit of extra time to talk with Jennifer about a hard time she’s going through, or she gives her a nice embrace, or shares resources with her, or acknowledges her good work publicly at a team meeting. Empowering gifts all the same. Giving in this kind fashion, studies show, will lead Kelly herself to feel delight through the activation of dopamine rich reward circuits in the brain (the second bubble). The expression of kindness will then move Jennifer to be more generous and collaborative in subsequent interactions with other members of their team (the third bubble). On this studies find that recipients of kindness themselves become more prosocially oriented in subsequent interactions.

Now things get even more interesting in our fourth bubble. Kelly’s original expression of kindness is likely to surface in team members’ casual, coffee cooler type conversations and minor acts of gossip. These conversations, my own research has shown, enable the team to form an opinion about the reputation of Kelly in her leadership position, as someone likely to advance or undermine their interests. In our example, her reputation is positive, and positive reputations themselves, studies show, lead to opportunities for innovation and influence. People also convey more esteem to those who have positive reputations in social networks (the fifth and final bubble), which inspires Kelly to further acts of empowering kindness. Kelly’s initial expression of kindness, seemingly inconsequential, ripples through her team, creating a foundation for enduring power.

Compassion just may be the most viral kind of action, one that spreads through social networks with remarkable power and ease. We have long believed that compassion is the antithesis of power and influence, but a new science of power is turning this conception on its head: we actually find real power in viral actions of compassion.

Share with

Related Resources