Stress. We’ve all experienced it. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say we’re all experiencing it. Because the truth is, stress is all around us. We often bounce in and out of various states of stress throughout the day – or throughout the hour. So, what should we know about this experience of stress? What happens in our brain and body when we’re stressed? How do we best navigate it and manage it? Let’s take a deep dive into the science of stress.

When talking about stress, it can be helpful to break it down into two parts: a stressor and a stress response.

A stressor is any event that triggers a stress response in the body. Anything can be a stressor! A big presentation, a sick child, or a frustrating morning commute can all be considered a stressor and can all trigger a response in the body.

A stress response is the way your body reacts to the stressor. Common stress responses in the body include sweaty palms, increased heart rate or rapid breathing. A stress response is your body’s signal that you need to change or adapt in order to manage the stressor.

It is important to know that stress is not all bad.

In fact, the truth is – most stress is good for us! We can categorize stress into three groups: positive, tolerable and toxic.

Positive stress is the stress that we get when we’re working on achieving a goal, or stress that motivates us to take a healthy risk. Think of that pre-exam stress or that nervous energy before walking on stage in front of a group.

Tolerable stress is serious, but temporary stress that is buffered by safe and supportive relationships. This might be something like getting a new job, moving to a new city or caretaking for an ill family member.

Toxic stress is strong, frequent or prolonged adversity without a buffering of safety and supportive relationships. Toxic stress might be getting evicted, working with a dangerous boss or managing a chronic illness.

You’ll see that, while we’ve given a few examples, we aren’t providing a comprehensive list of what stressors fall in each category. That’s because it would be impossible! What is tolerable for one person may be toxic for another. It is not the stressor that determines the severity of the stress. How a body responds to stress depends on a variety of internal and external resources.

Internal resources are things like:

External resources are things like:

The more resources available to a person, the better able they are to handle stressors and keep stress from becoming toxic. Of course, these resources are not available equally to all people, and this helps explain why some individuals and some communities face greater amounts of stress than others.

To better understand how stress and the body are connected, we need to understand a few simple concepts. Let’s start with the brain.

You brain is your central processing network. It guides everything that you do: your body’s movements, your decision making, and your emotions. There are, of course, countless things we could say about the brain. But let’s keep it simple and focus on just a few.

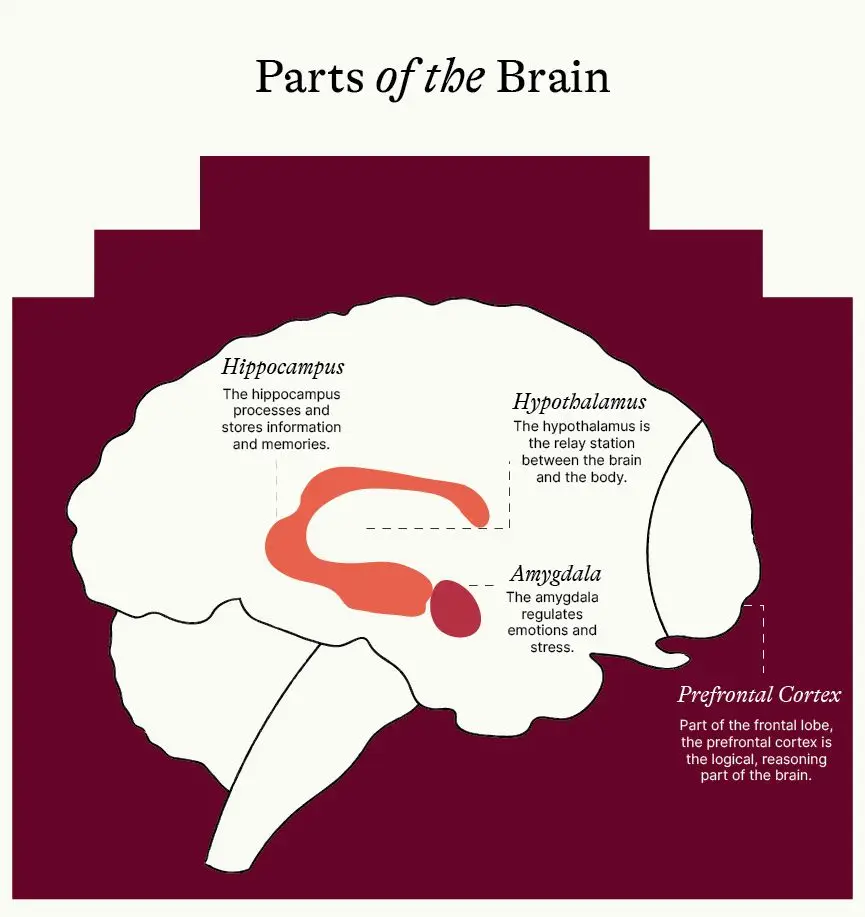

There are four main parts of the brain we want to explore: the amygdala, the hippocampus, the prefrontal cortex, and the hypothalamus.

The hippocampus processes and stores information and memories. It’s your brain’s filing cabinet.

The prefrontal cortex is the logical, reasoning part of the brain. Think of this as Brain HQ.

The amygdala is the emotional center of the brain. It regulates emotions and stress.

The hypothalamus is the relay station between the brain and the body. It receives and sends signals in the form of neurotransmitters.

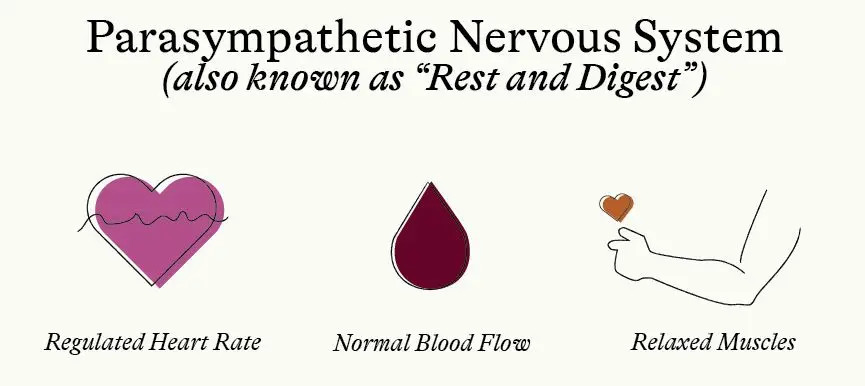

The body has something called the autonomic nervous system, which regulates involuntary body functions. Within this system, there is the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. Both systems are involuntary and happen without reason or logic, but understanding them helps make sense of our brain and body’s reactions.

The sympathetic nervous system is often called the fight or flight response. It is activated when we face a threat and causes a physical involuntary response, such as increased heart rate and blood flow, and tightening of muscles. When this system is activated, the parasympathetic nervous system is not functioning at full capacity.

The parasympathetic nervous system is often called the rest and digest system. It affects the same body functions as the sympathetic nervous system, but in a different way. It works to slow down certain responses, allowing the body to rest and repair.

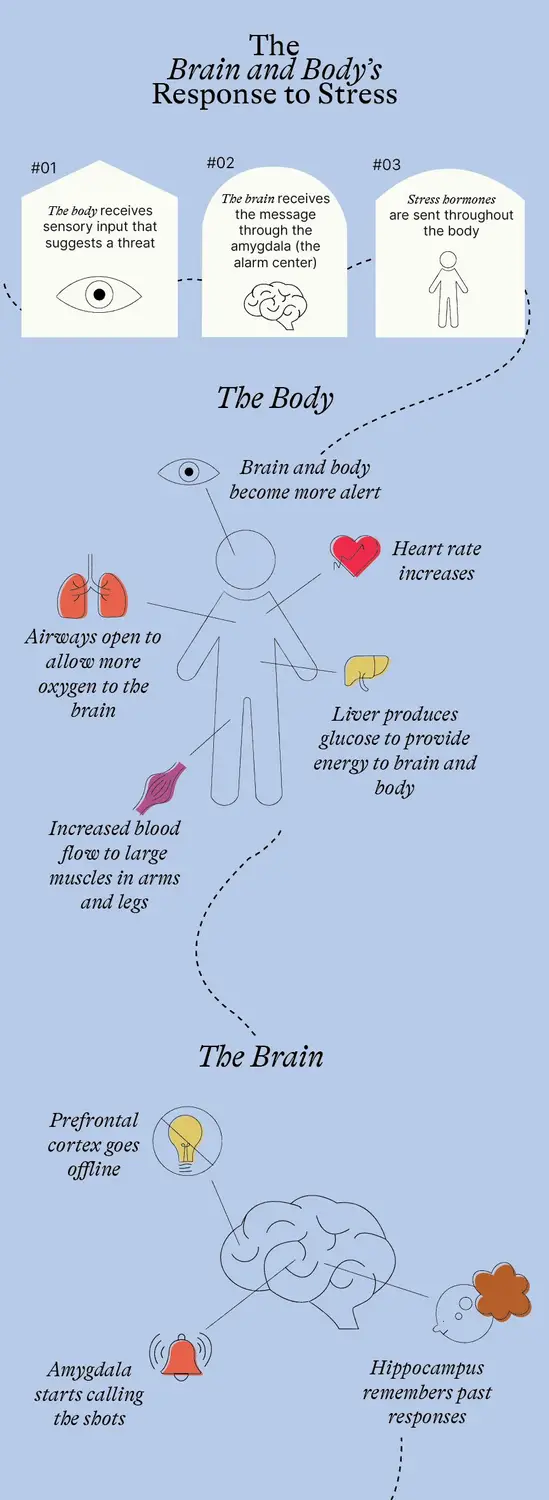

So here’s how it works. The body receives sensory input (it sees something, feels something, etc.) that suggests there is a threat. This message is immediately sent to the brain, where it first lands with the amygdala. (The prefrontal cortex – the reason and logic part of the brain – also receives sensory input. However, the amygdala, in the center of the brain, gets the message first. This means it’s not possible to stop the amygdala from initiating a stress response when it senses a threat… even if the prefrontal cortex would be able to identify it, make sense of it, or decide it’s not a threat at all.)

When the amygdala receives the message that there is a possible threat, it sounds the alarm. It signals the hypothalamus to release stress hormones that send a message to the adrenal gland letting it know that it’s go time. The adrenal gland, located at the top of the kidneys, releases hormones called epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine into the blood stream. It’s at this point that the stress response becomes a full-body response.

Epinephrine increases the heart rate, sending blood to the large muscles in the arms and legs. It also opens airways, allowing for more oxygen to flow into the brain. Additionally, epinephrine increases blood sugar levels which leads the liver to produce more glucose to provide energy to the brain and body. At the same time, norepinephrine causes increased alertness, arousal and attention and also causes blood vessels to constrict, maintaining the body’s blood pressure. Think of it like this: the brain determines something is dangerous and gives the body all the muscle power, oxygen and energy it needs to tackle the threat. Now, while all of this is going on in the body, there are other things happening in the brain. Once the amygdala senses a threat, it takes over. This means that the prefrontal cortex goes ‘offline’ and the amygdala and hippocampus start a conversation about how to respond to the threat. The hippocampus jumps in, providing memories about previous stress responses. These memories will help determine if the correct response is fight, flight or freeze.

Everything we just described is what happens in the immediate seconds following a determined threat. For example, your boss unexpectedly asks you to stop by to chat about something. If this is a normal routine and doesn’t cause any stress, the brain and body will continue as normal. But if something about this registers as a threat, perhaps previous experience with this boss, or bosses in general, the brain and body may go through the process described above before you can even say, “Sure, I’ll be right there.”

Then what happens?

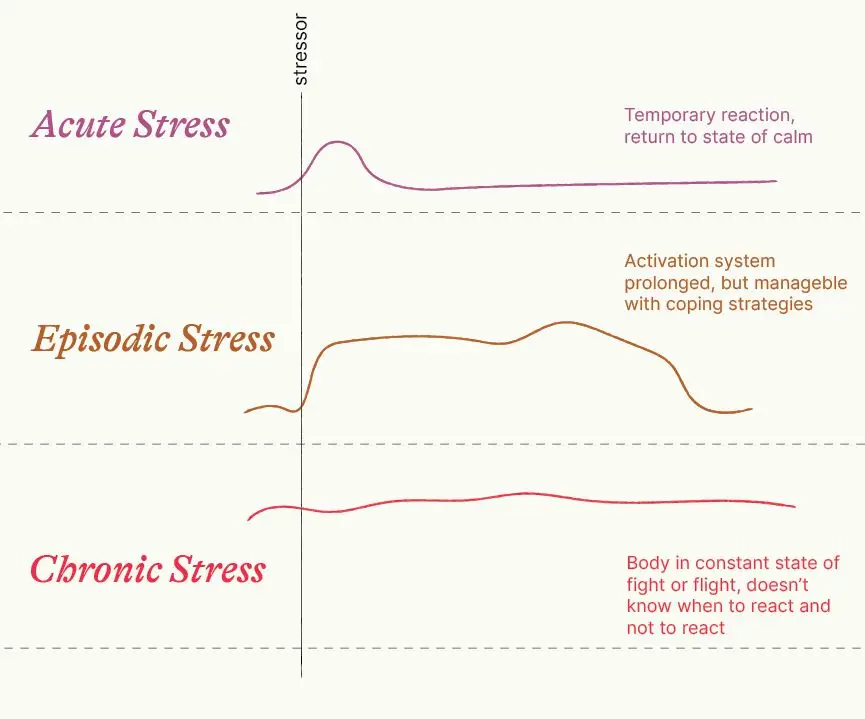

This is where we revisit the types of stress. The body is designed to manage positive stress. It recognizes that something is happening, but also determines that it is safe. The body will have a temporary reaction, as described above, and will return to a state of calm pretty easily or quickly. Deep breathing, a brief walk or a phone call with a trusted loved one can send the brain the message that it is safe.

Tolerable stress is more prolonged and lasts longer than just one instant. In this situation, the activation system is prolonged, and it doesn’t return to a state of calm as easily. This type of stress may pile on top of itself, so just when one stressor is getting managed, another thing comes along. But what keeps this stress tolerable are coping strategies that activate the parasympathetic nervous system that can help manage it. It takes more effort to reduce tolerable stress, because the system has been activated for longer. This means that it is not as effective at determining whether something is a threat and may start to identify more and more things as stressors.

With toxic stress, the stressors don’t stop or there is no end in sight. In this case, the brain is on such high alert that it can start to lie to the body and tell the body that it is not safe, even if it is. The stress response in this case doesn’t know when to react and when not to react. The body can be in a constant state of fight or flight, meaning the sympathetic nervous system stays activated, and anything from a loud noise to someone brushing up against you in passing can trigger a stress response. This stress is the most difficult to manage because it requires not only the lessening of stressors, but also the regulation of the stress response system in the body to bring it back to a state of calm.

We can’t talk about stress in the body without talking about a few other hormones. We’ve already discussed adrenaline (epinephrine) and norepinephrine, above. But there are quite a few hormones at play in the stress response system!

Hormones are chemical messengers for the body. They are produced by the endocrine system (in the body) and travel via the blood stream. We are made up of over 50 different hormones that control our body’s biological processes. For the purposes of stress, we will focus on a few key hormones.

Cortisol is nicknamed “the stress hormone”. It’s an important part of the body’s built-in alarm system. During moments of stress, cortisol is released in the body, which does a number of things, including prompting the liver to produce glucose, which helps the brain with alertness and attention. It also signals to the non-emergency functions of the body to take a back seat – things like digestion and growth.

Oxytocin is sometimes known as the “love hormone” because it spikes when we have positive social interactions with those around us. What does this have to do with stress? Research shows that oxytocin can dampen the fear response (that old fight-or-flight instinct), essentially making you better able to face a stressor. But not only that. Oxytocin is released as part of the stress response system to encourage you to connect with other people. This is called the “tend and befriend” response. It is one way that people manage stress, by connecting with people and communities that are important to them.

Our brains are wired for acute stress, followed by a recovery period. We are not wired for stressor after stressor after stressor. This is why chronic stress is difficult for the brain and body to manage – they weren’t built for the job!

Chronic stress can lead to allostatic load, also known as “wear and tear” on the body as a result of stress.

The body has regulation systems in place to keep it healthy for survival. Homeostasis is a steady state; it is when the body’s internal, physical and chemical conditions are regulated. This is our body at optimal functioning – body temperature, blood sugar levels, energy, hormones and more are constantly adjusted to respond to changes both inside and outside the body to keep them at a normal level.

Allostasis is the body’s way to achieve stability through change. It is how the body works to get back to a state of homeostasis. Rather than just responding to the environment, allostasis is predictive, meaning it is flexible and anticipates the body’s needs before they arise, budgeting resources accordingly and adapting promptly to meet the needs. For example, a bear preparing to hibernate for winter will build up fat deposits in the body. This is an example of an allostatic state.

You can imagine that it takes considerable energy to predict future outcomes. In a situation where upcoming stressors are predictable, the brain and body can manage this fairly smoothly. But at times where there is uncertainty or the stress is not resolved, the situation might become chronic and result in allostatic overload.

Situations that may lead to allostatic overload include:

Allostatic overload often results in difficulty sleeping, lack of energy, generalized anxiety, social impairment or generally feeling overwhelmed with the demands of life.

We have talked about the immediate impact of stress on the brain and body. But what happens in the long term?

It is important to remember that everyone experiences stress – and that most stress is good for us! When our body experiences positive and tolerable acute stress, it builds the capacity for future stress responses. In essence, the hippocampus stores memories that help us later recall successful responses for the next incident.

And remember, stress is made up of two parts: stressors and stress responses. Stressors are an inevitable part of life. There’s no way to make it through life – or even just a day – without encountering stressful moments. Our stress responses, on the other hand, can be positive. They can help us navigate life and give us valuable tools for managing what comes our way.

However, it is not surprising that when we have too many stressors and/or unhealthy or insufficient stress response systems, we can encounter damaging long-term effects. Chronic stress can lead to serious health problems, such as heart disease, depression, and anxiety disorders. It can also suppress the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight off infections and diseases. Chronic stress can impact the following areas:

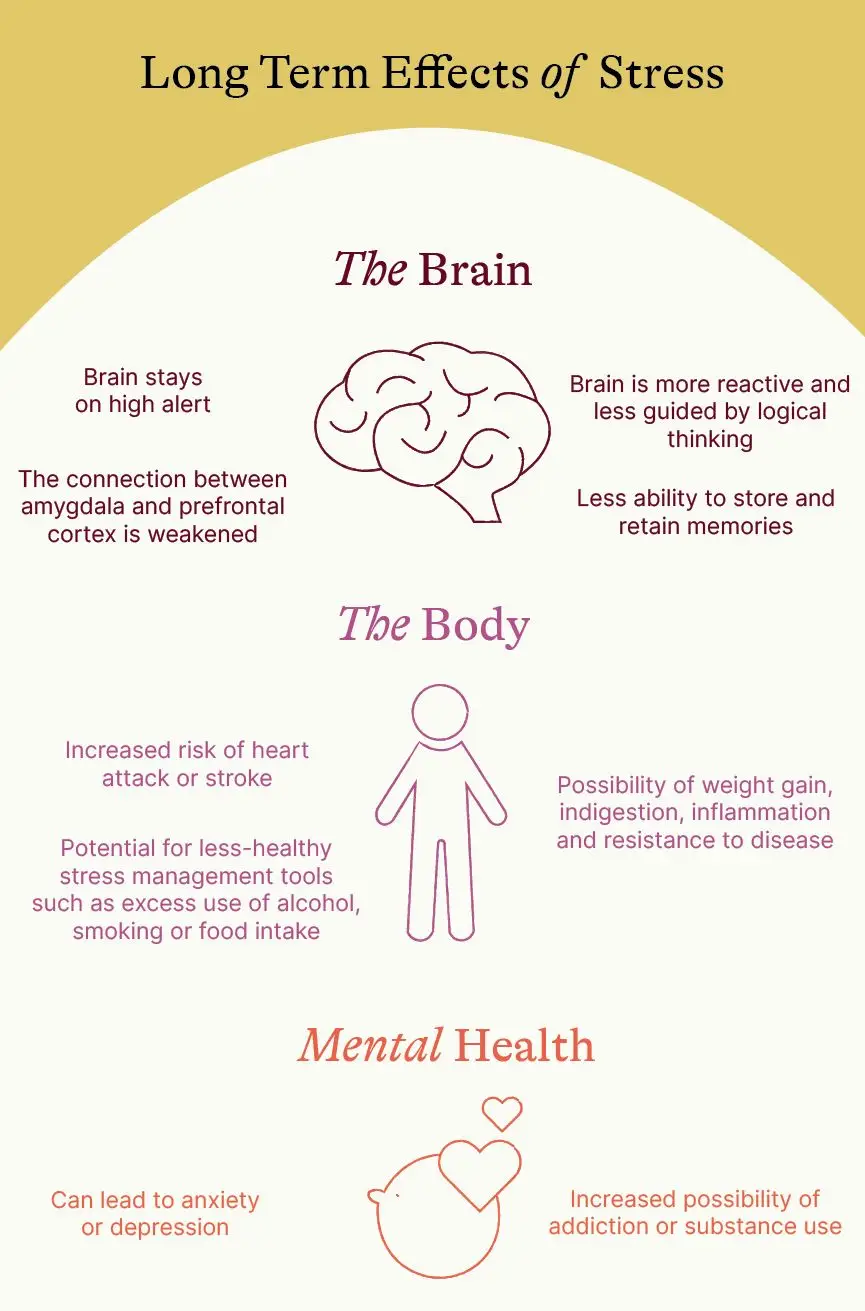

The Brain

Too much stress can put the brain on high alert, and as a result, the connection between the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex can become weakened. When this happens, the prefrontal cortex is less able to do its job (logic and reason), meaning the brain may continue to be more reactive and less guided by logical thinking.

Excess levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, can affect the hippocampus’s ability to produce new brain cells and repair damaged cells. The result? It can diminish the brain’s ability to learn and retain memories.

The Body

Most people are aware of a link between stress and the heart. We know that heart attacks and heart disease are often linked to higher levels of stress. What’s the science to this? When the heart experiences repeated surges of adrenaline (epinephrine), it can damage the lining of the blood vessels. This can increase the risk of heart attack, stroke and hypertension.

Another reason these two are linked is because some people experiencing stress rely on less-healthy stress management tools, such as excess use of alcohol, smoking or food intake, which can also lead to heart problems.

Stress can also have other physical responses, such as weight gain, indigestion, inflammation, and resistance to disease.

Mental Health

Allostatic overload or chronic stress can also affect a person’s mental health. It’s not hard to imagine that when someone is in the dark tunnel of chronic stress and can’t see the light at the end, it can take a toll on emotional wellbeing. Prolonged stress can lead to anxiety, depression, addiction, or substance use. It can be difficult to untangle these experiences. Does stress cause an anxiety disorder, or does an anxiety disorder cause stress? Is a person’s substance use an unhealthy coping strategy for a stressor, or is the substance use creating or extending the stress response? While the science is not definitive, there is evidence in the field of mental health to show that chronic stress can cause or contribute to other mental health challenges.

But don’t worry, it’s not all bad!

In her book, The Upside of Stress, Dr. Kelly McGonigal cites numerous research studies that show how we feel about stress affects how stress impacts us. The long and short of it: if we can shift our mindset to embrace stress – not as something to get rid of, but something to understand and leverage – we can become stronger, smarter and happier. Sounds too good to be true? It turns out that it’s not so much the stress that is hurting us, it’s our belief that stress is bad for us. If we can shift our mindset, we can shift our outcomes.

How to Make Stress Your Friend TED Talk

In this article, we’ve explored the science of stress. Most of the brain and body’s reactions to stress are automatic and involuntary. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t learn them! The more we know about how our brain and body respond, the better we’re able to understand and manage our reactions in the future. This knowledge also gives us the opportunity to manage our stress in order to limit the impact of stress on our bodies and support our mental health.

Share with

Related Resources